¶ Printing Press Revolution

¶ The Printing Press

Our story begins in Europe at the dawn of the 16th century.

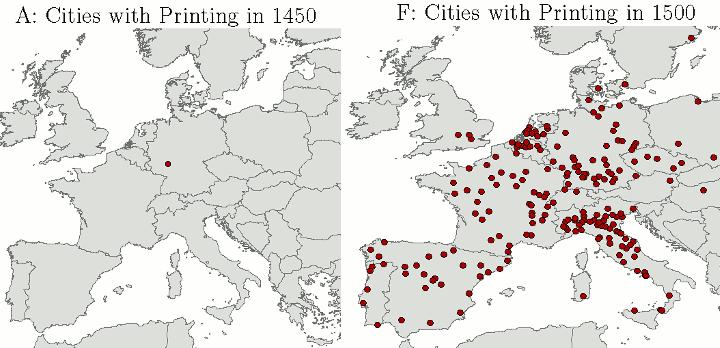

The Catholic Church, then the unified church of all (Western European) Christians, was the dominant political force. The printing press, the first mass communications technology, had been invented 60 years before.

As the Church grew in scope and power, so did its financial needs. By 1500, the selling indulgences - a formal reduction of eternal punishment for sins committed during ones life - had become a critical funding source for the church.

Indulgences had been around for centuries, the printing press completely changed the stakes: now indulgences could be mass produced. And with mass produced-indulgences, the scale of what was possible increase exponentially.

For example, in Spain, indulgences funded the war against Granada and even contributed to Christopher Columbus’s famous voyage.

¶ St. Peter's Basilica

The renovation of St. Peter’s basilica had been high on the Vatican's list for a long time; in 1506 the project began.

It quickly became clear that the issue wouldn’t be engineering, it would be funding.

By now, indulgences were a thriving industry. Clergy would contract with entrepreneurs who would print the documentation, and also would advertise and support an indulgence campaign.

In 1517, Archbishop Albert of Mainz commissioned a campaign that would reach Wittenberg.

¶ Martin Luther

In Wittenberg, a small, quiet university town, a young Augustinian friar and university scholar named Martin Luther lived and worked.

A deeply religious man, Luther joined a long line of men passionately seeking to reform the church.

By 1517, his focus was on indulgences.

¶ The Ninety-five Theses

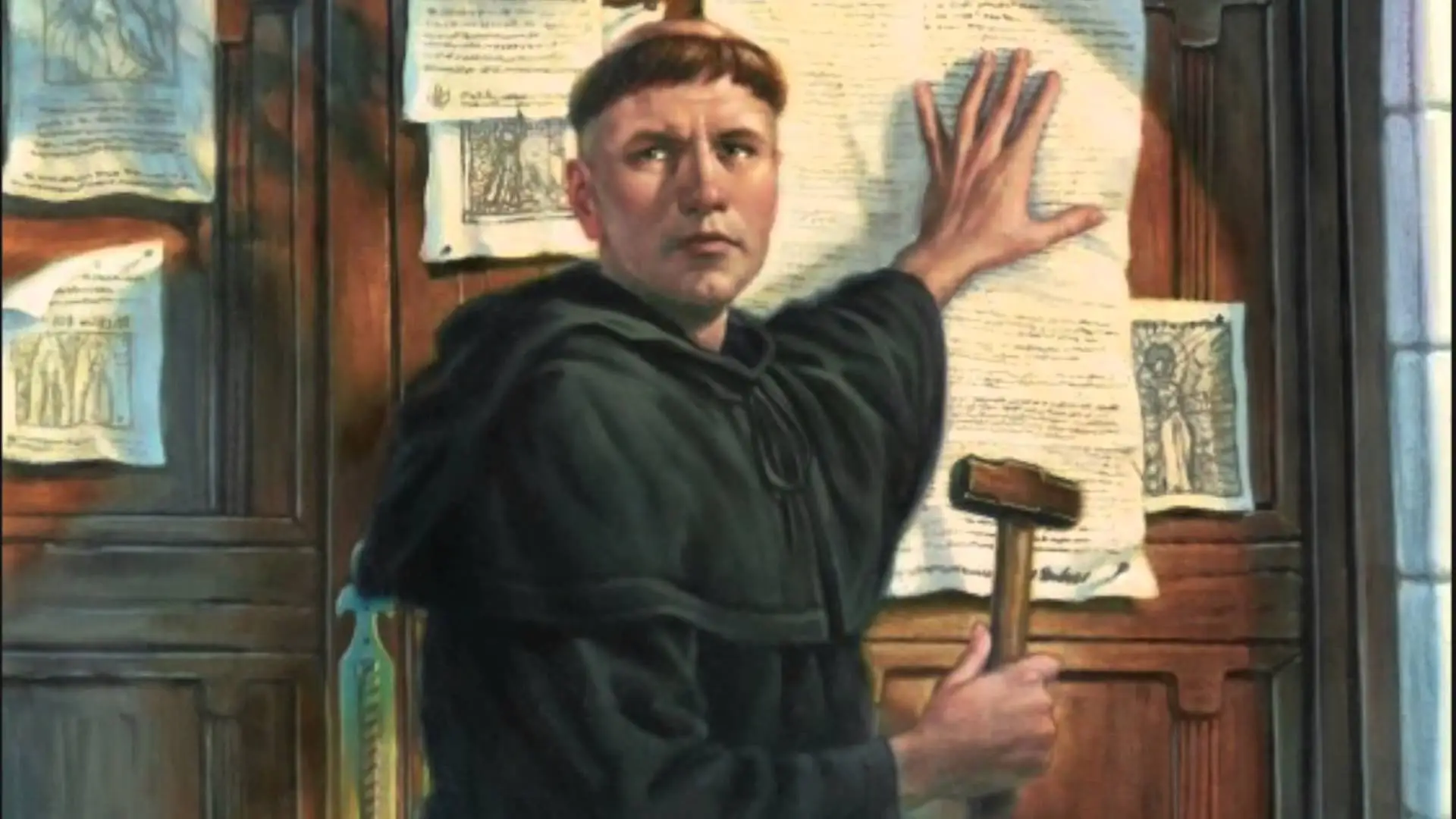

In October 1517, Luther walked over to the church of Wittenberg with a copy of his latest work, "Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences."

The door was papered over with layers of flyers; one more paper would be insignificant.

The work, also called the Ninety-five Theses, was a simple call to academic debate. No one was nearby to notice… and even if they were, what another call to debate in a university town?

And yet, this was the beginning of a reformation that reshape the religious world.

¶ Going Viral

After Luther left the church, he then sent a copy to Bishop Albert, his superior in Mainz. While he feigned politeness, his outrage over the bishops indulgences and his implicit criticism was clear.

Albert was not amused.

Luther also sent copies of the Ninety-five thesis to other, more receptive audiences. A friend in Nuremberg printed many copies of the work, which quickly became widely sought after.

Within months, Europes leading intellectuals were discussing the Theses.

¶ Fighting in the Comments

In response to its shocking popularity, Johann Tetzel - the entrepreneur responsible for this particular set of indulgences - published a response.

Luther countered with his second pamphlet "Sermon on Indulgences and Grace", this time writing in German.

Many regard this 2nd pamphlet as the true starting point of the Reformation.

The Ninety-five Theses were written and discussed in Latin, the language of academic debate. If debate stayed in Latin, any reform movement it sparked would remain in the educated elite.

Both pamphlets were instant best sellers.

Luther had a knack for writing compelling and entertaining content.

¶ Industry

But Luther was only half the equation; the other half were the printers.

The printing industry was a risky industry: books required major upfront investment and had no guarantees that any market would exist for any given book.

This is still true today; imagine how much more difficult things would be if most people were illiterate.

In general, printers were not interested in the religious debate; many printers would print both Luther’s (and followers) and the Church’s responses.

In contrast to a book or manuscript, Luther's content was very cheap/quick to produce and had an insatiable market. Luther had exactly the right combination of ideas and writing skills to convey them to mass audiences. Printers had the economic incentives to identify and meet demand.

And so, they worked together to create a brand new market: a reading public.

¶ Global Prominence

From his first two works, things happened quickly.

As Luther grew in prominence, many people rose to object to his arguments. Luther responded to many of these with public pamphlets and letters, spiraling into increasingly extreme and vitriolic responses.

Timeline

- 1518: Luther was an unknown professor in a small town writing for an academic audience

- 1519: Luther had become the most famous person in Europe's German speaking regions

- 1520: Luther was the best selling author since the invention of the printing press

It's hard to overstate just how dominate Luther was. From 1517 to 1525, Luther was published 1.4k times, 11x more than the next most prolific author.

To say he held a monopoly would be an understatement; most of the next most famous writers were his students.

¶ The Reformation

This was the essence of the reformation, both Luther’s contribution and the force that would eventually spin out of his control.

As his works spread and audiences grew, his arguments grew increasingly extreme.

And, the printers knew (and know), extreme content sells extremely well.

By the time the Ninety-five Theses reached the Vatican, the decision was as easy as it was harsh: the work was heretical and Luther must be dealt with. This would draw the lines over which participants would square off with increasing violent rhetoric.

Beginning with the German Peasants War of 1524-25, over the next ~130 years 100,000s of people would die in brutal wars fueled by a combination of religious fervor and petty power grabs. 25 - 40% of the people of (what is now) Germany perished.

The conflict would forever split (Western) Christianity.

The violence would eventually marginalize an increasingly erratic Luther, who would eventually be eclipsed by the next generation of reformers (especially John Calvin).

Eventually, Luther would die a sick old man, his brain and reputation marred by antisemitism and rage.

¶ Communications Revolution

Without printing, the Reformation could not have existed.

The mainstream logic goes something like “printing created mass communication, ending the church's ability to control what people think. Reformation is inevitable!”

But I think that is a smooth-brained take.

History is not inevitable, it happens in a specific way for specific reasons.

What Martin Luther and his printers unleashed would metastasize into religious conflict that spanned generations.

But the intention was much more simple.

Much more capitalist.

Luther opened Pandora’s box not only with his ideas, but also by proving there was a market for even more radical ideas that would inevitably lead to violence. In the end, the printers would commit to supplying that market, regardless of the consequences.

The printing press was invented around 1440. ~75 years later, a small group of innovators took that same invention and built a new business model.

That model would directly lead to a multi-generational war and remake the world.

The internet was invented around 1990.

¶ Resources

Source Material - Twitter Link

Source Material - PDF