¶ The Dot-Com Bubble

¶ Author's Note

2022 is an incredibly volatile and stressful year, especially in the crypto industry. We are experiencing the collapse of a bubble, one that continues to deflate long after any of us thought possible.

There is a lot to take away from the lessons of the dot com bubble, and a lot of critically important differences. But there is one thing that is the same:

The noise of the market obscures the technological magic that is happening right before our eyes.

Originally published on the Flywheel Podcast as a video essay, available here.

¶ Background

In the United States, the 1990s begins in the aftermath of an economic recession.

During the first part of the decade, congress made major changes to raise taxes and restrict government spending. This had the net effect of reducing government borrowing, freeing capital for private investment.

Outside of the economic realm, the 1990s was an incredible time for computers and computer science. Technology was getting cheaper, smaller and more capable. Household computer ownership jumped from 15% to 35% by 1997.

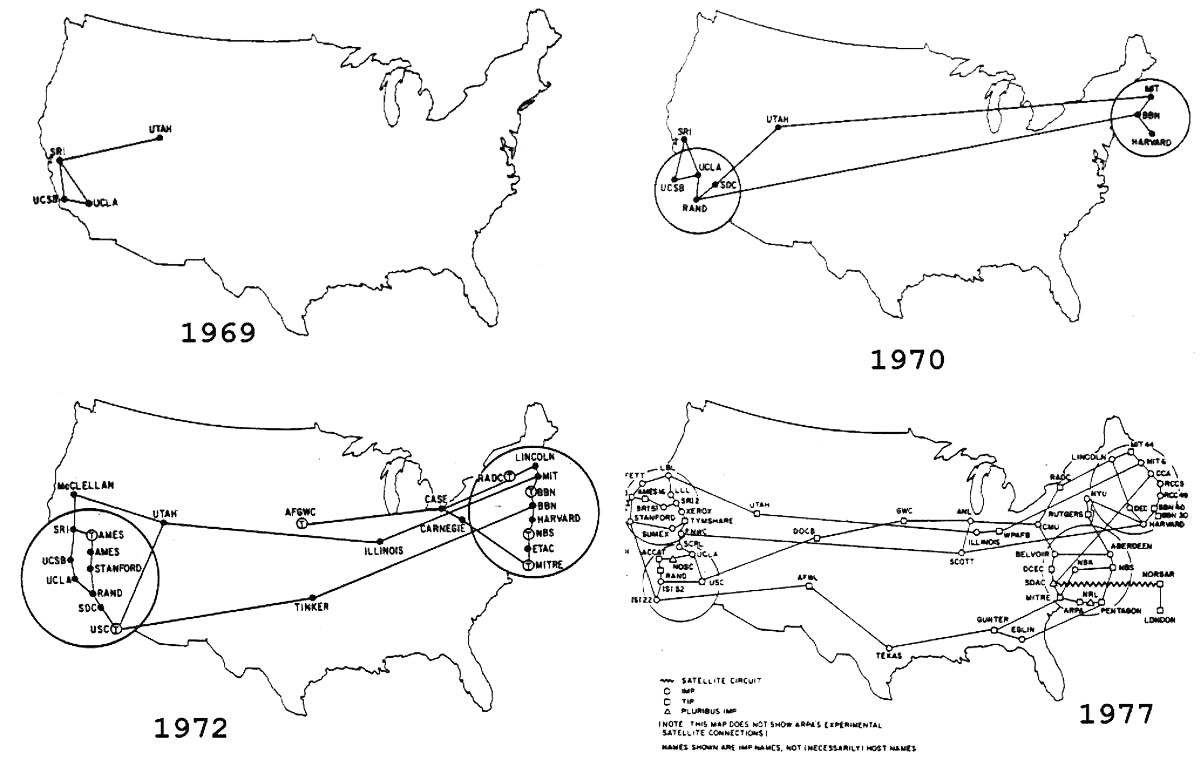

And a few folks, backed by Department of Defense spending, had spent the last decade networking a few major universities and other primitive data centers together.

¶ The Birth of the Dot Com

If you are looking for a specific moment, it’s in October 1994. That’s when Jim Clark and Marc Andreesen launched the Netscape browser, allowing free and open access to the World Wide Web.

The moment this global network of computers can finally be called the Internet.

Netscape not only gave open access to the Internet, it fundamentally defined what it meant to be an internet business. Or more specifically, a dot com business.

Netscape was launched in October 1994, by August of the next year it went public. 16 months after the company was formed, Clark and Andreeson listed Netscape stock for $28 per share, and that was only after a very last minute decision to double the initial price from $14.

On the actual IPO day, the stock got as high as $75, before ending the day at $58.

The great California gold rush of 1849 began when James Marshall found gold at Sutter’s Mill in the Sierra Nevada mountains.

The great California gold rush of 1995 began at the close of trading on August 9th, 1995 when Netscape, an “internet” company with basically 0 revenue, some users and an incredible amount of excitement was worth $2.9B dollars.

¶ The Internet Gold Rush

And so things took off, and took off quickly.

Before long, all it took was adding “dot com” to your name, paying a college nerd to put up a website, spin a story about an ever-connecting-data-driven world, and you could EASILY raise tens of millions of dollars for your dot com startup.

Here are just some of the examples that illustrate the irrational exuberance of the dot com era:

- Webvan, founded in 1996 (interestingly by the founders of the Border’s bookstore chain), was a company that would allow you to order your groceries online and have them delivered within a 30-minute window.

- In total, Webvan raised ~800MM at a peak valuation of $4.8B on a CUMULATIVE revenue of $395k and losses of more than $50MM

- TheGlobe.com, founded in 1995 by a couple of Cornell students, was one of the very first attempts at social networking, think more like Reddit than Facebook.

- TheGlobe rapidly became part of the popular zeitgeist in November 1998 after their IPO posted the then largest single day gain. They had listed their shares for $9, which had spiked as high as $97 before ending at $63.50 for a market cap of $840 MM, despite never (before or after) making a profit.

- LookSmart, founded in 1995 in Australia by a husband and wife pair of McKinsey execs, was an early search engine competing against Yahoo and Alta Vista.

- By 1999 LookSmart was the 12th most visited website on the planet. In August, the founders leveraged a $55MM Microsoft contract into an IPO at a $1B valuation. By March 2000, LookSmart was worth $7B without any meaningful new business

¶ Pets.com

But perhaps the best known example of the dot com bubble was Pets.com.

Pets.com was a relative latecomer, launched in November 1998. But boy they made sure to make the most of their time within the bubble.

In its first fiscal year, Pets.com spent $11.8MM in advertising to generate $620k in revenue. Even before the costs of advertising, the website was selling products for about 1/3 of the cost of the merchandise.

In a normal context, no rational investor would give Pets.com a second glance. But this wasn't a normal context, it was the dot com boom... and Pets.com was the perfect dot com company:

.com was in the name!!!!

And so in June 1999, Pets.com secured its first round of financing: ~$50MM for ~50% of the company.

If you are to ask basically anyone what they remember the top signal of the dot com bubble was, the majority people are going to give you the same answer: the Pets.com super bowl commercial.

Pets.com spent $1.2MM to air whatever THAT was during the Y2K Super Bowl. I don't think inflation adjusted numbers are a good way to get a sense, so let me put it this way: a 30 second commercial in 2022 cost $6.5MM.

Now look, there have been a ton of stupid commercials, and most have completely lost to history. But this commercial was SO DUMB that it broke them outside of the nerdy tech world and became part of the general conversation for a few weeks…

…long enough for pets.com to IPO and raise $83MM less than 1 month later.

From its first days as a public company, there was blood in the water. They would last 9 more months.

On November 7th, 2000, pets.com stopped taking orders. 2 days later they laid off 225 out of 320 employees. They had burnt through the entire $300MM they had raised.

¶ Bursting Bubble

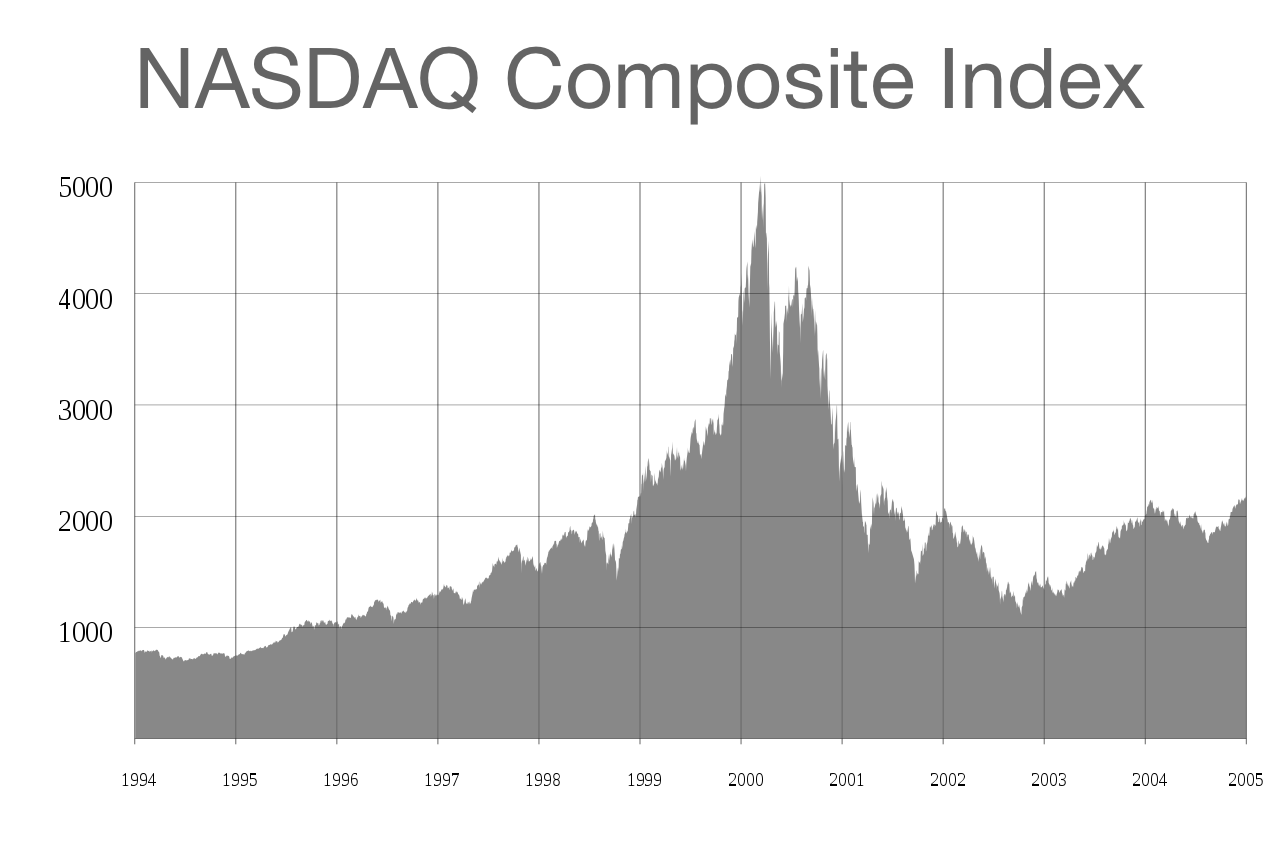

And it wasn’t only pets.com. By late 2000 the dot com bubble was undeniably bursting.

Webvan, TheGlobe.com, LookSmart and basically every other dot com darling was either in flames or already collapsed.

The companies that survived, names like Amazon, Google and others you still know today, saw their stock draw down by more than 75%.

And macro? While the tech industry was not doing itself any favors, the geopolitical situation seemed like it was conspiring to make any relief impossible.

A recession in Japan, rising interest rates, increasing skepticism about tech/internet companies… the environment was bad and every day was getting worse.

¶ World in Flames

And then fall 2001 came, and the world changed forever.

4 planes took off the morning of September 11 and never made it to their destination.

Everyone’s lives changed, and the world became a worse place on that day.

And in its aftermath, giants began to fall.

The capitalist gods among us were revealed to be complete and utter pretenders, sitting on a throne of lies and crime.

We exalted these executives as being made of something different, rubbing elbows with politicians and altruistically crafting legislation.

But it turned out they were not only defrauding customers, but using their monopoly position to extract profits, no matter the cost.

In November 2000, just weeks after 9/11, Enron collapsed, bringing Arthur Anderson down with it.

¶ Top Signals

The dot com bubble came out of nowhere, swept into the hearts and minds of billions of people, built everyone into dreamers and then collapsed into a fiery heap.

Netscape launched in 1994 and the bubble was undeniably deflating by the end of 2000.

Everything happened so fast.

It was so easy to get caught up in the hype, just part of the culture to throw some money at these meme-stocks and then begin dreaming about cars and yachts.

If you were paying close enough attention, you saw some troubling signs early on. Some things that screamed “you are in the realm of 23 year olds lighting money on fire, you should leave while you still can.”

LOTS of things that, in retrospect would be called top signals.

But when that sock puppet showed up in the Super Bowl, the holy alter of American Capitalism, shilling bags of dog food for half the cost it took to manufacture it, that was the moment that crossed the line.

And once we hit that moment, there is no coming back.

¶ Exponential Change

Yes, macro was terrible.

Yes, individual actors were exacerbating the situation.

Yes, everyone was way over leveraged and whatever pain had to come was multiplied. But what it really comes down to is human psychology.

The same phenomena that transformed Jim Clark and Marc Andreeson’s mediocre dial-up browser into a multi-trillion dollar asset bubble was able to take it down basically overnight.

From earth, to the moon and back all in about half a decade.

For the vast majority of people, the dot com boom is remembered with some nostalgia for a time of wide open dreaming and a lot of pain and regret for the wealth lost chasing millions.

While it depends who you ask, most people who got sucked into the dot com boom ended up poorer and unprepared for the recession that it created.

The individual human experience of the dot com boom can be described as a little exuberance followed by a lot of punishment.

¶ Collective Progress

But here’s the funny thing about the way life works…

While it’s true that the median experience of the dot com boom and bust was pretty miserable, the collective experience was pretty remarkable.

It fundamentally changed the lives of every single human that walks this earth, stretching on into an infinite future.

The dot com bubble was a fire that burned hotter and brighter than anything we had ever seen before. While it burned millions in the process, it was the crucible that created the modern internet.

Google was founded in 1998.

Amazon was founded in 1994.

PayPal was founded in 1995.

The companies that would form the pillars of our modern internet were formed out of the same substance that create Webvan or TheGlobe.com.

Many companies did not make it, but all laid the foundation for what was to come.

People in the 1990s fell head over heel in love with internet and then that love faded, but internet did not care.

It just kept on growing slowly, relentlessly, until it completely transformed our lives.

¶ Today's Internet

Think about your day today.

Your iPhone woke you up. You check you messages. You use GPS to get to work. You spend all day writing emails, having zoom meeting and browsing reddit. On your way home you order groceries, which are delivered and waiting for you. Then you search for a new recipe and learn how to make an excellent dish. Then you stream some video content before you go to sleep listening to your favorite podcast.

None of this was possible before or even during the dot com bubble, but the dot com bubble created the world you have today.

¶ Visionaries

¶ False Prophets

Everything we used to make fun of dot com founders… the dreams, the ambition, the audacity… everything ended up kinda working out just the way they said it would.

It’s just that they weren’t the guys that could get it done.

That’s usually how it works out, the loudest ones are great at raising attention and capital, but they VERY rarely are able to actually deliver.

So who can deliver? It’s not the founders of Webvan or LookSmart.

It’s not the Do Kwons or the Su Zhus or the SBFs of the world.

The people who are truly going to change the world are much quieter.

¶ True Harbingers

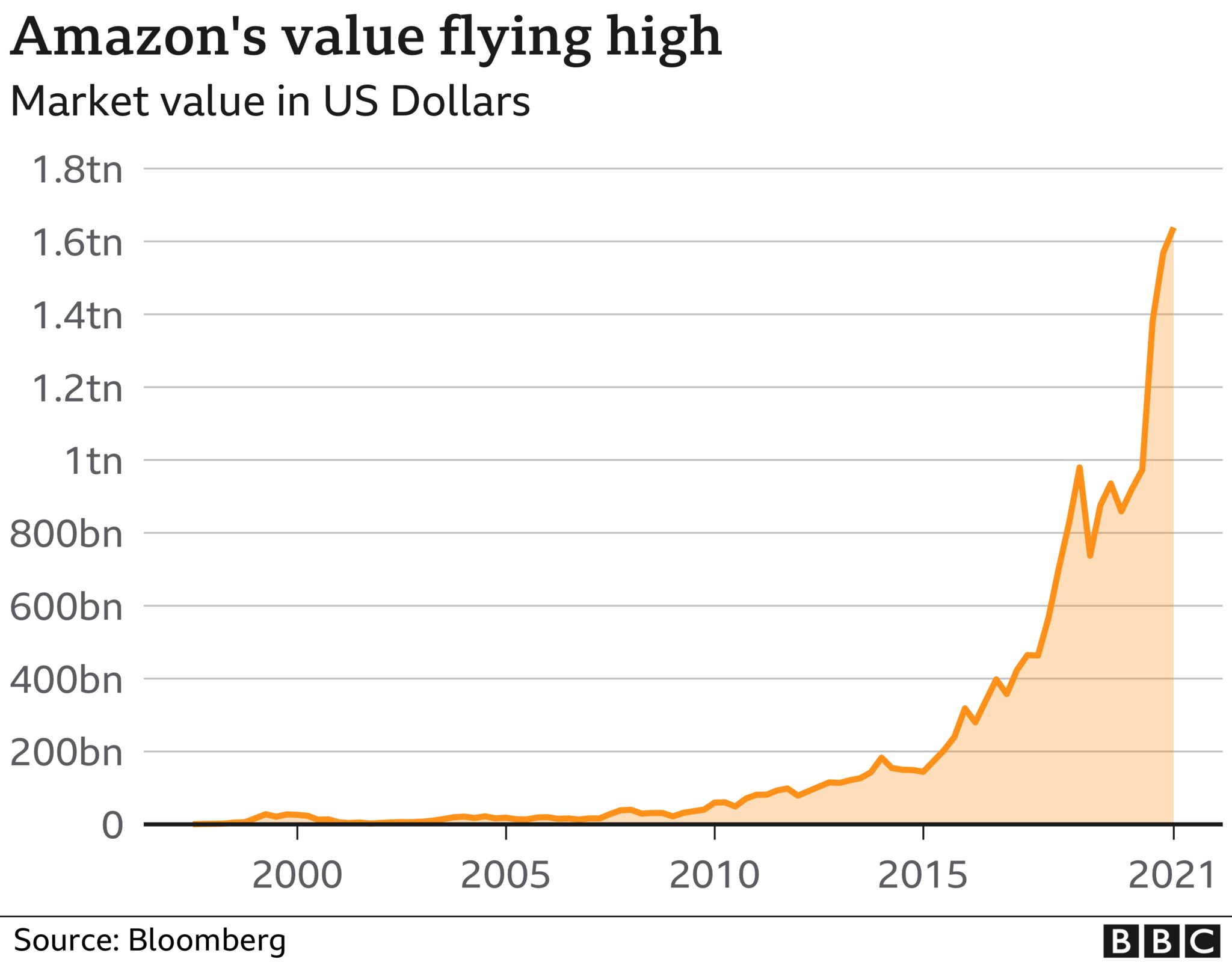

Let’s take a look at the winner of the first (and second) cycle of the internet: Jeff Bezos.

Now I’ve never met him, never spoken to him, I’ve barely read anything he’s written or said. But here’s something I am absolutely certain of: in 1993 when, Jeff Bezos was sitting in his office at the hedge fund of D. E. Shaw & Co, he literally saw the future.

He saw the same future that all the moonboy CEOs saw, the same one we are sitting in right now.

But Jeff Bezos didn’t walk into the public square and declare that he was going to build the future the Jetsons could only dream of…

In 1994, when he left his job to start an internet company, he did not set out to start the worlds largest, most important logistics and cloud computing company in the history of the world.

He just wanted to sell books.

¶ The Next Bezos

As I look around for this cycle’s Jeff Bezos, I am looking for quiet builders who can see the future.

I am looking for people and teams that not only can master the metagame being played today, but use that mastery to command a leading position in the next meta. I am looking for dreamers who can see decades in the future, but are only willing to talk about ideas that can be implemented within the next quarter.

And I am looking for leaders that are building more than products, that are building institutions.

When I look around for this cycle’s Jeff Bezos, there seems to be one clear fit: Sam Kazemian.

But we are not here to discuss crypto’s champions, we are here to discuss top signals and, more specifically, what we can learn from them.

¶ Unexpected Lessons

In 2000, after pets.com put a sock puppet on national TV and created the world’s best example of a top signal, the market fell apart.

Billions of (paper) dollars vanished overnight.

Pets.com alone burned through $147MM in the first 9 months of 2000 before throwing in the towel and lighting the rest of the equity on fire via bankruptcy.

But here’s the interesting secret behind Pets.com, perhaps the biggest failure in the entire dot com bubble.

Of all the people invested in Pets.com (including, unfortunately, the investing public), the single biggest investor is (probably) pretty ok with how things turned out.

For you see, the same guy who lost the MOST money on the DUMBEST dot com company actually ended up being the same guy who basically won the ENTIRE thing:

¶ Takeaways

There are two important lessons of the dot com bubble:

- the business of technology is incredibly vulnerable to manic behavior and bubbles

- the most important factor of success is survival

Winners know how to play the long game.

¶ Resources

Source Material - Flywheel Podcast Episode

Other Material - Twitter Link

Other Material - PDF